When Canada implemented the Online News Act in June 22, 2023, I’m sure news publishers didn’t think Facebook would pull all news from its pages. Oops.

Aimed at making big tech – Meta and Google – pay revenues to news publishers, the Act wasn’t looked at fondly from big tech, although their response differed.

Meta, which owns Facebook was pretty clear about its feelings. In a company blog post, Meta insisted that news companies share links to their news on Meta’s platforms to support their own advertising revenues. “The legislation is based on the incorrect premise that Meta benefits unfairly from news content shared on our platforms, when the reverse is true.”

As soon as the law came into effect, Meta began pulling news from its pages. Implications of the decision were global; Canadians did not see news on their pages, whether it was local, national, or international. News agencies outside of Canada continued to post their stories, they just wouldn’t be seen in Canada. Now you will see this message on old news links: Read article: Not available on Meta platforms. I have no doubt other countries are looking at Meta’s response, including New Zealand.

Google’s take was a bit different, offering $100 million annually to “accredited” publishers, which was eventually accepted. I don’t know how payments work as it’s still in development but it includes a board of sorts to administer. It will be interesting to see how the money from Google flows but my guess as well as some others is larger publishers will benefit most while smaller news outlets will get the remnants.

What I want to know is if federal legislation and Meta’s decision affected Canadians’ knowledge of emergent news. In this case study, we will look at a real-world situation, and an organization’s current strategies to inform the public. We are going to evaluate if strategies need to adapt to the fast-changing world of social media, and whether Facebook is a tool they should use.

Let’s get into it.

It’s been almost a year since the Online News Act was signed. To understand the effects of this legislation I use a winter cold snap that affected Albertans as our case study, analyzing how an organization, the Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO), worked to get an emergent message about power consumption to the public, how news publishers reported on it, and how Meta’s removal of links may have affected public awareness. This is not an exhaustive study but hopefully the discussion provides insights for professionals about Facebook’s platform as a medium for public discourse.

The findings in this case study are my own. My opinions come from my own personal and professional experience, academic research process using a variety of sources including academic papers, reports, polls, social media studies, news articles, and data, to provide as well of a rounded analysis as possible, and hopefully, to remove any of my own bias in the process. I have provided links to online sources within the text and a bibliography to credit academic sources at the end of this post. This case study is not a criticism of news publishers, Meta, nor AESO’s strategies; it is being done to help others consider their communication strategies in emergent situations and to think critically about changes affect emergent communication strategies.

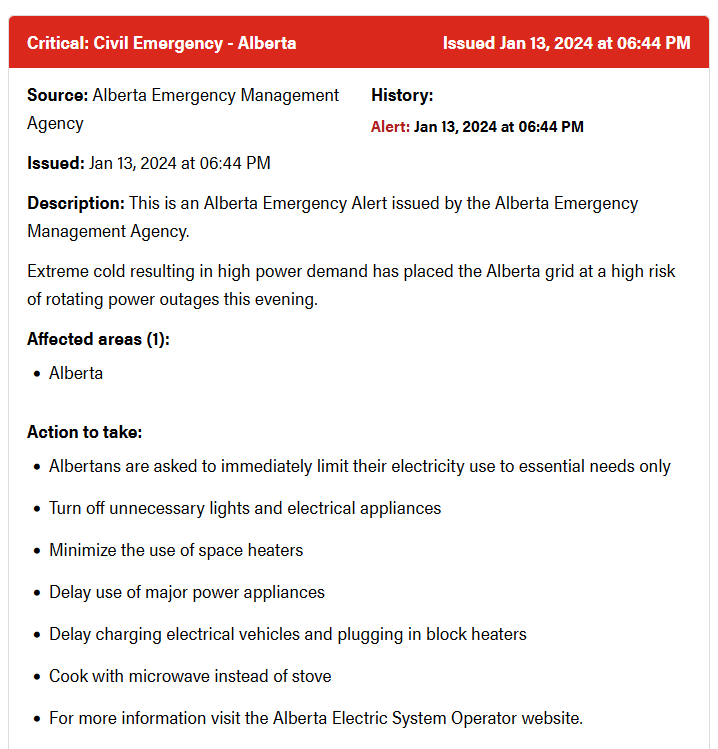

In the first weeks of 2024, Albertans faced an extended cold snap that dropped into the minus-30s and minus-40s. Schools were shut down, electricity use skyrocketed, and Albertans bundled up to weather the storm. In the second week of 2024 things really started to get serious. On Jan. 13, 2024 at 6:44 p.m. an Alberta-wide emergency alert issued. Albertans were asked to immediately reduce their energy consumption or risk rolling blackouts across the province.

Extreme cold temperatures put such a strain on Alberta’s electrical grid that AESO saw demand exceed available power. They were ready to flip the switch. Thankfully the emergency alert worked! People rose to the occasion and the electrical system was able to catch up and the AESO thanked the public for their hard work.

Thank you, Alberta! Your conservation efforts quickly reduced electricity demand and the risk of rotating outages. A special shout out to our System Controllers, industry partners and the Government of Alberta for keeping the power flowing and all Albertans safe and warm tonight. pic.twitter.com/eJ2fN4JcQk

— AESO (@theAESO) January 14, 2024

Here’s the problem, the strain on the electrical system was already threatening available power. On Jan. 12 , AESO issued its first level three grid alert, the highest, on its home page and on X (formerly Twitter ) followed by recommendations on how to conserve energy followed by recommendations on how to conserve energy. This was much more serious than people realized. We had four grid alerts from Jan. 12 to Jan. 15 and while rolling blackouts didn’t occur, the severity of the situation prior to the emergency alert was high. During this time, news agencies were reporting on the grid alerts but one of the channels publishers used to deliver the news – Facebook – was no longer around. This missing medium affected public awareness. Let me explain.

High power demand due to extreme cold, two large natural gas generator outages, and very low renewable power on the system have prompted the AESO to declare a Grid Alert. Find information on Grid Alerts here https://t.co/eQAHOzfzgI pic.twitter.com/1pzOJt2T1L

— AESO (@theAESO) January 12, 2024

Jan. 12 grid alert above and Alberta Emergency Alert below

This is an Alberta Emergency Alert issued by the Alberta Emergency Management Agency.

— Alberta Emergency Alert (@AB_EmergAlert) January 14, 2024

Extreme cold resulting in high power demand has placed the Alberta grid at a high risk of rotating power outages this evening.

Briefly, there are two outward-facing communication channels I can see that AESO uses. One is through grid alerts on its homepage where up-to-date information is issued. As a bonus users can sign up for alert notifications. The other is on X where a grid status update is posted and users can comment and/or repost the information. It’s possible AESO made use of digital highway signs seen on major Alberta highways, but I don’t have access to that information.

These communication tactics were generally quite effective, and before the Online News Act, got the word out exactly as intended. AESO would employ the use of key statements about the problem and news publishers would receive that information. Reporters would then transmit that as news to the public. This was a mutually beneficial arrangement: for AESO, reporters would spread the message, reducing the workload for AESO communicators; and for publishers, AESO’s grid alert meant web hits to news pages, which would in turn benefit advertising revenue. To drive people to their websites, news publishers would post a story link onto their social media pages, which included Facebook. This was and is common practice for news publishers around the globe. Studies have found that Facebook is an important referral source for these companies (Bar-Gill et al., 2021; Majid, 2023; Nielsen & Fletcher, 2022; NW et al., n.d.; Schmidt et al., 2023; “Social Media and News Fact Sheet,” 2023).

That’s all changed in Canada with the Online News Act. We know the decisions affected news publishers. Did it affect the public?

Considering the size of Facebook with over three billion monthly users, there is evidence to support public awareness of emergent news through the social media site. As a former multimedia editor, when I shared a breaking news story on our Facebook page, I would watch the number of online visitors spike dramatically each time. Social media was an extremely important strategy in driving users to our website and I wasn’t the only one.

In one Australian study (Bailo et al., 2021), news agencies confirmed one third of referrals came from Facebook. The study is based in Australia, but I would argue that company strategies are similar in Canada. The authors point to the fact that Facebook can shape discourse on many levels, including politics and journalism. Academics call it a winner-take-all or winner-take-most situation where tech giants like Meta and Google hold most or all the information (Bailo et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2023). So, if a company like Facebook holds such influence because of the large (that’s an understatement) number of people using it, then an organization like AESO needs to be part of the conversation. What AESO had no control over is that over time news publishers followed their audience to Facebook over X.

News publishers’ strategies fall into what Nielsen and Fletcher state as an over reliance by publishers on “secondary gatekeepers for distribution,” (2022), that being media like Facebook and X. By extension organizations like AESO have relied on news publishers to divvy out the news through their news delivery strategies, which included social media. In this case study, I think it’s important to recognize that X used to be the best way to get emergent information to the public. It required a short number of characters in a post and it was extremely easy to transmit information. Those days are over in Canada because the number of users on X is significantly smaller than Facebook (X sits at around 619 million monthly users). As Nielsen and Fletcher put it, “most publishers get a significant share of their online traffic via platforms, and some publishers a majority,” (2022) by posting their news story links on Facebook.

Again, this is not a criticism of AESO. No one could have foreseen the full effect of the news act and Meta’s decision. A previous system that worked well for AESO saw a paradigm shift; Facebook’s users may have noticed news was gone, but they may not have changed their browsing habits.

Considering influence of Facebook, we should talk about a communications concept called medium theory as it gives us a better understanding about different media and their influence on societies. Remember three billion monthly users?

Understanding the available mediums to transmit information to the public is critical for any organization. According to Meyrowitz (2008) there’s a micro and a macro level to medium theory. A good example of “micro” is in the way a camera influences a politician when they are speaking to the public, and a good “macro” example relates to how certain media influences a society rather than the individual (Meyrowitz, 2008). The Online News Act, Google’s systems and Facebook are great examples of macro influence because they affect entire swaths of the globe. For AESO, medium theory is important to keep in because it’s the system operator for electrical delivery to the entire province. The information AESO needs to share affects Albertans’ daily lives and a platform like Facebook is more than a place for a status update. “…that such media must be looked at as creating new social settings, settings whose influence cannot be reduced to the content of the messages transmitted through them,” (Meyrowitz, 2008).

One study looks at medium theory in relation to crisis communications and how organizations manage public expectations (Tække, 2017). This wasn’t a crisis for AESO, more of a communication problem, but the article has merit for this study, “in the functionally differentiated society, an organization must be able to communicate in all society’s different symbolically generalized communication media.” (P. 187, 2017). Now, this doesn’t mean AESO should open social media accounts on every single social media page. It makes no sense for AESO to open a Kijiji account for instance. Facebook is not the only medium, and not every organization should be on Facebook, but it shouldn’t be ignored. It’s an interesting time to be alive. We no longer live and work in silos and people gather information from so many places. Organizations are in a position to shape discussion through these mediums and also reduce confusion.

There are contradictions in my research, some of which may be my own confirmation bias in believing that AESO should rely on Facebook, and some I feel academics aren’t asking the right questions.

1 – Despite the research, studies can’t get a true picture of the number of referrals from Facebook to news websites and as a result, academics advise caution against “overestimating the prevalence of Facebook referrals” (Schmidt et al., 2023).

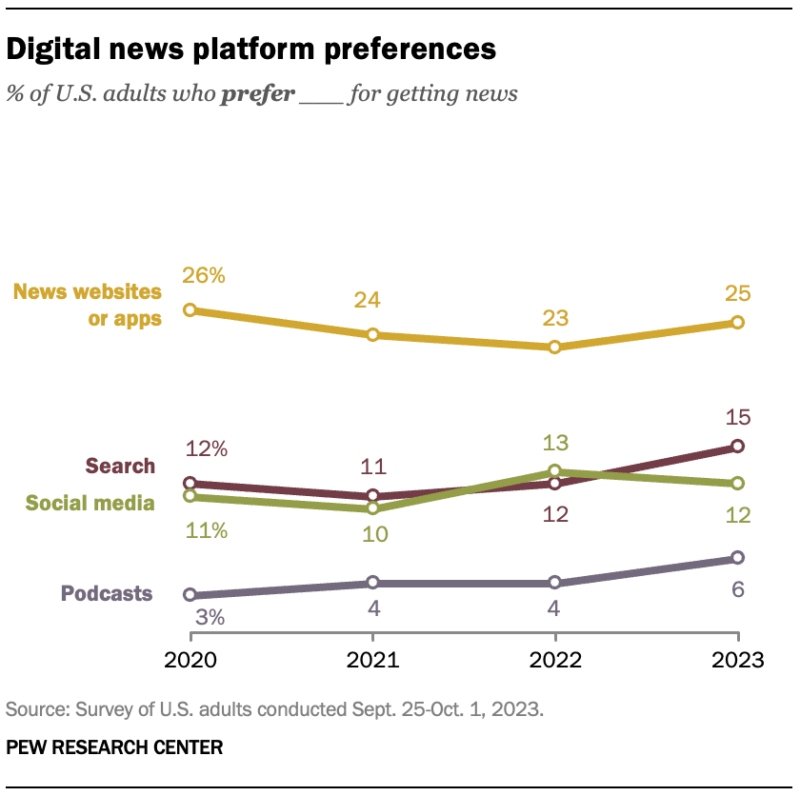

2 – Polls and reports suggest the majority of digital users access news sites directly rather than through social media. According to the Pew Research Centre, 25% of U.S. adults go directly to a news site or app, 15% through a Google search, 12% through social media, and six per cent through podcasts.

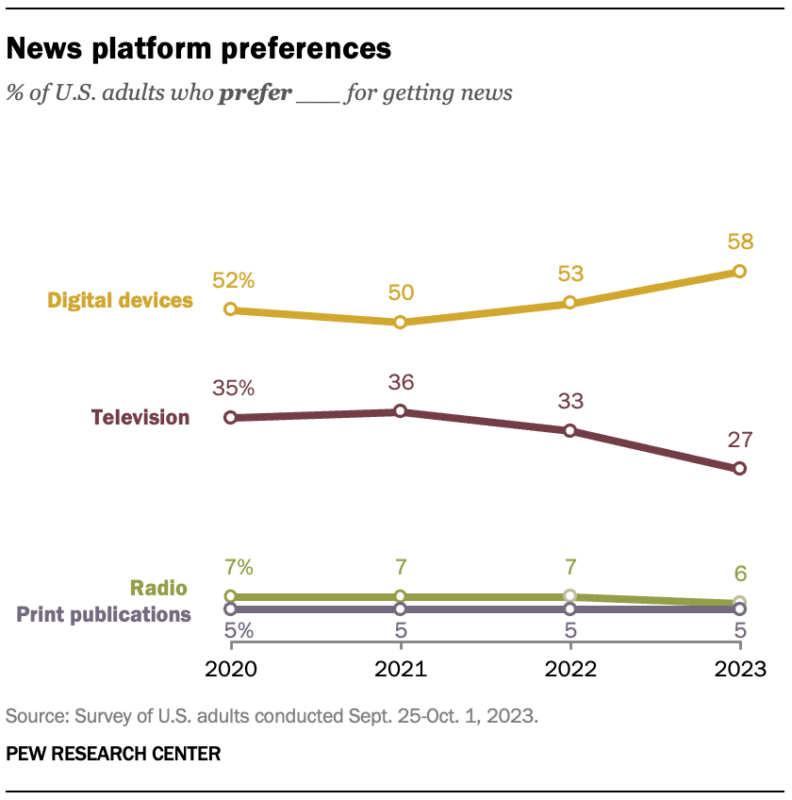

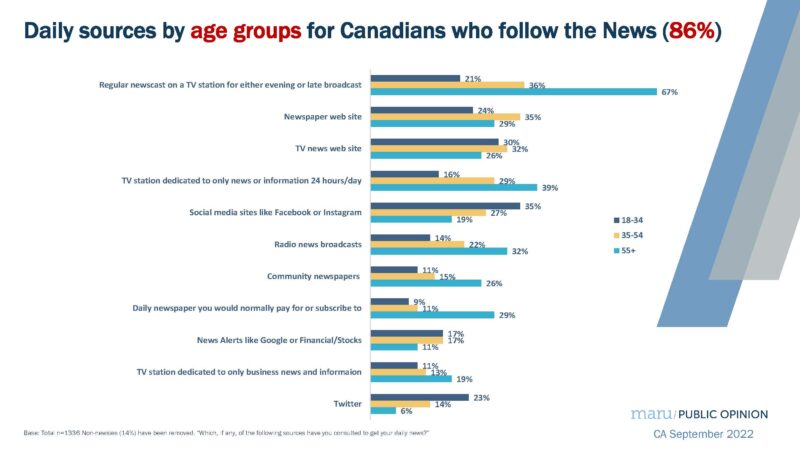

For younger demographics, those numbers do start to change with social media being the big source of news for the 18- to- 34-year-old demographic. Despite maru’s poll, Pew’s research of American news consumers suggests television is not as high in the news food chain.

If the maru poll is accurate in that television news is the place where people get their news, why then are news agencies seeking compensation from Facebook referrals and why is Facebook the only other organization besides Google the Online News Act addresses? The actions of companies and legislators counter these studies.

Accounting for my own bias, I expected referral numbers to be more in the 60 per cent range but Australian one study confirms the number to be around 30 per cent (Majid, 2023). Despite my bias, the numbers in Australia are likely similar in Canada and that is still a significant amount of market share. For the maru poll, I just don’t see Television news as the biggest source of news for Canadians. Factor in breaking news, which can happen at any time, and I imagine the numbers would be quite different.

Numbers aside, there is one more important factor about news consumption: for the most part, people trust traditional news. According to an Ipsos poll (Trust in Traditional News Rebounds, But Canadians Worry about Loss of Local News and Use of AI in the Newsroom, 2023), insert pic 63 per cent of Canadians trust traditional news. This is good news (ahem) because when publishers report on something, this suggests a general trust of the process. Maybe it has something to do with the legacy of traditional news, that there’s a person behind the story, digging for information and there’s an editor checking on the story (for now anyways, AI is changing that landscape).

The problem is Facebook and Google account for a large chunk of referrals for news publishers. In addition, people aren’t “looking” for emergent stories. Breaking news is something that is currently happening or developing. Generally, people don’t go to a news website or television news station to wait for unknown stories to break. So, when a breaking or emergent news event occurs, if people aren’t sitting on the news source, there is a good possibility they might see it from somewhere else, like Facebook or though their network of friends. Currently there is one way to “share” a news story on Facebook in Canada. Users can screenshot a news story, post and comment on it, or they can share links from a non-news website, but the organization is limited by the “trust” factor. For example, during the grid alerts issued by AESO leading up to the province-wide alert, Alberta’s Premier, Danielle Smith posted on her Facebook page about the strain on the electrical grid.

The Premier’s Facebook posts show just how Facebook’s removal of news looks on its pages. When you click the below embedded link, it takes you to her Facebook post, but there are no links.

The problem is, and I say this respectfully, politicians aren’t a traditional news source and AESO’s message was limited by that fact. Users did share the premier’s post, but it was filled with political comments from pundits and critics. The need to reduce energy consumption became muddied with troll-like diatribes readily found on social media. Here’s an important thing to remember about social media:

“In an environment where many internet users rarely visit news sites directly, distributed discovery provides news publishers with an opportunity to reach more people, and to serve existing audiences across additional channels.”

(Nielsen & Fletcher, 2022)

In Canada news publishers no longer have that luxury, but non-news agencies do. Organizations hoping to be heard will want to be part of that distributed discovery. Why is understanding Facebook news referrals and news acquisition important? It helps shape the communication strategies organizations make, and it helps with our understanding of the importance of medium theory, that of the interaction and influence of a medium on a society (Meyrowitz, 2008). A medium like Facebook should be part of an organization’s communication process or at the least strategists should evaluate the merits of using the medium. It’s not for every organization, but it’s an important part of the equation.

The final piece to this case study is in the grid alerts data. Was this the first time Albertans received an emergency alert related to rolling blackouts? Yes.

AESO’s historical alerts are available for review:

1 – Looking at the history of Alberta-wide emergency alerts for the last seven years (online archives don’t go past seven years), none were issued because of a grid alert.

2 – Since 2006 the AESO has issued 19 Energy Emergency Alerts at level 3, which is defined as “Firm load interruption imminent or in progress.”

3 – Nine of those EEA3s were during winter months, five in December 2022 and four in January 2024.

4 – The 2022 events are likely the best comparison, especially on Dec. 20 and 21 as those dates saw extreme cold conditions like what we faced this past January. The power draw on the electrical grid was at its highest for both those events.

5 – There were other EEA3s issued in April 2024 due to a variety of reasons and no Alberta emergency alerts were issued, so one could argue that this whole exercise is unnecessary. However, if we look at December 2022 compared to January 2024, the length of the grid alerts is important.

6 – The longest length of EEA3 in 2022 was 3.91 hours, while the longest EEA3 in January 2024 was 6.51 hours. This suggests Albertans did not realize the extent of the problem.

7 – The Alberta Emergency Alert saw immediate action from Albertans. This suggests people will answer a call to action if they know about it. I don’t think they were truly aware of the grid challenges January 2024.

Considering the number of users on Facebook compared to X and the actions of Albertans once they were aware of the problem, I see a direct connection between Meta removing news from its pages and Albertans’ awareness of breaking news events. Albertans became a victim of the legislation and Meta’s decision.

An interesting side note to this analysis is when AESO issued a grid alert this past April due to a natural gas power plant going offline, rolling blackouts did occur in Edmonton. AESO hosted an online media briefing with a spokesperson. This suggests, and I have no doubt this is in a constant state of review at AESO, that the organization is looking at different ways of communicating important updates to the public.

With the implementation of the Online News Act and Meta’s subsequent removal of news from its pages in Canada, Albertans were left in the dark about an important infrastructural problem. The influence of Facebook on society (for better or worse) is clear; the decisions Meta makes have far-reaching effects and organizations need to consider it as one of their channels for information dissemination.

The influence of Facebook notwithstanding, there are two important factors organizations need to keep in mind when planning: 1) not every organization should use Facebook; and 2) they should use channels other than Facebook where people can confirm information being shared and to reduce reliance on one source of information. From an organizational perspective, it really comes down to the why of it. Why are we using/not using Facebook and should we? It’s really about the users. I know my own habits as a news consumer. I don’t make a point of going to a news website or television news show to wait for a breaking news event to be reported, it’s an impossible task. With at least one third of news site visits coming directly from Facebook, and with the proverbial tap turned off, organizations can no longer rely on traditional news as their main channel for information dissemination. This has been a long time coming for news publishers but the Online News Act exacerbated an already tenuous situation for traditional news. Change in today’s media world is rapid and it’s ongoing. Organizations must make it a priority to evaluate the strengths of mediums they use to inform the public or they will get lost in the shuffle.

Anderson, M. (n.d.). Social media causes some users to rethink their views on an issue. Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/07/social-media-causes-some-users-to-rethink-their-views-on-an-issue/

Bailo, F., Meese, J., & Hurcombe, E. (2021). The Institutional Impacts of Algorithmic Distribution: Facebook and the Australian News Media. Social Media + Society, 7(2), 205630512110249. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211024963

Bar-Gill, S., Inbar, Y., & Reichman, S. (2021). The Impact of Social vs. Nonsocial Referring Channels on Online News Consumption. Management Science, 67(4), 2420–2447. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3637

Majid, A. (2023, April 13). Search vs social: How referral traffic to news sites has changed in five years. Press Gazette. https://pressgazette.co.uk/media-audience-and-business-data/media_metrics/news-referral-traffic-breakdown/

Meyrowitz, J. (2008). Medium Theory. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication (1st ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecm064

Nielsen, R. K., & Fletcher, R. (2022). Concentration of online news traffic and publishers’ reliance on platform referrals: Evidence from passive tracking data in the UK. Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media, 2. https://doi.org/10.51685/jqd.2022.015

NW, 1615 L. St, Washington, S. 800, & Inquiries, D. 20036 U.-419-4300 | M.-857-8562 | F.-419-4372 | M. (n.d.). Social Media and News Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

Schmidt, F., Mangold, F., Stier, S., & Ulloa, R. (2023). Facebook as an Avenue to News: A Comparison and Validation of Approaches to Identify Facebook Referrals. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/cks68

Social Media and News Fact Sheet. (2023, November 15). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

Tække, J. (2017). Crisis Communication and Social Media. A Systems‐ and Medium‐Theoretical Perspective. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 34(2), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2451

Trust in Traditional News Rebounds, But Canadians Worry about Loss of Local News and Use of AI in the Newsroom. (2023). Ipsos. https://www.ipsos.com/en-ca/trust-traditional-news-rebounds